Editorials

Machinarium’s Narrative Machinations

November 8, 2012, Author: Adam Boffa

Amanita Design’s Machinarium starts by throwing you into a big pile of trash. You must literally rebuild yourself in a dump before you can go any further, and when you do, there are few details given about your predicament and the world you inhabit. Mostly you are left alone to inspect every element of the robotic ecosystem around you, with just the occasional glimpse of a memory to spur you on.

Minimalist narratives are not new to gaming. Both old-school and modern games have made wonderful use of storytelling tactics that omit details in favor of creating a sense of ambiguity, leaving the rest up to the player’s interpretation. The indie game scene, in particular, has taken up this mantle in recent years, creating games that spin just enough of a narrative thread to keep the player intrigued without giving anything else away.

However, Machinarium’s approach to the minimalist narrative is pretty unique.

The game contains very little text, and instead relies heavily on contextual clues to relate gameplay information to the player. Additionally, the many robots that inhabit Machinarium’s lovingly-realized mechanical world do not speak in any recognizable manner. They make noises and pantomime things to each other, but without text and speech, a lot of the developments we’ve made in storytelling over the past few centuries become irrelevant.

Amanita Design’s solution is a simple visual cue: a thought bubble that occasionally pops up from your character’s head that relates, in short animations with little fanfare or fluff, some brief memory or another. The drawings are intentionally crude and the tone is often sort of silly, but these short sequences provide almost all of the information we have about the characters and their circumstances.

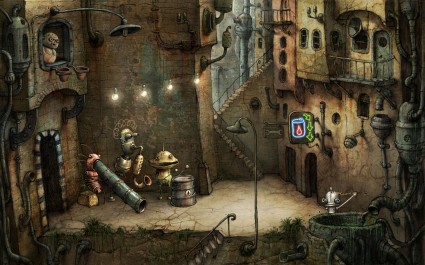

The classic jazz trio: saxophone, didgeridoo, and barrel.

Early on, as our robot hero hides behind a big furnace, a rotund robot with a mean smirk marches into the room and triggers a memory. In it, this same new robot stomps all over a sandcastle our hero is making and then chucks a bucket over our hero’s head, laughing as he walks away. It is completely ridiculous and it tells us everything we need to know: this dude is a jerk and we have reason to hate him. Bullies should be stopped. Let’s find out what he’s up to.

Eventually we lose his trail for a bit and might start to wonder what our other motivations for moving through this labyrinthine city are. Not too much further along, we see another menacing figure and a new memory pops up. This one shows the new guy ruining our day in a different way, but the important part is the robot girl sitting next to us as it happens. She gazes at our hero dreamily and seems to be having a lovely time with him. We haven’t seen her before in person, so we must be searching for her. Again, that’s all the information we need.

What makes this little gimmick work is that it allows the player to fill in the narrative and (more importantly) emotional gaps in their own, personal way. We do not know anything about the big guy who stomps on our sandcastle, but we can all tap into our own social experiences to find just enough seething hatred for bullies to project onto him, to keep us engaged and chasing. We might even start filling out a backstory in our minds to help out.

I do not know what the digital clock equivalent for "Sun-Symbol-past-IX" is.

Similarly, when our plucky avatar finds his special lady and they reach out to hold each other’s hands, we don’t need to know the specifics of their relationship. The little bit we saw in his memory is enough to tug at our heartstrings and maybe even remind us of someone we know who we’d search high and low for in a giant, mechanical metropolis filled with androids. The words aren’t important because the emotional message rings clear.

It’s a risky maneuver. Machinarium benefits from having a world with exceptionally well-defined aesthetics and tone. Each new scene seems to be filled with history and personality, and the musical score illuminates the emotional underpinnings incredibly effectively. This means the narrative work can take a bit of a break as the player gets overwhelmed, in a wonderful way, by the world and its sounds.

It all works together, though, and the bursts of remembrance that populate the experience act as the crucial glue. Almost all of the characters’ personas and their relationships to each other are related to us in these moments, creating the sympathy the player needs to keep plugging along even when frustrated by the game’s puzzles.

Machinarium is not a game that is primarily concerned with story or character development. It is certainly more focused on its puzzle-oriented gameplay and richly-detailed world. Its approach to narrative is worth admiring, though. By filling in just a few gaps with memories from the main character’s life, the developers are able to tap into the emotional experiences and the imaginations of their audience. The result is a story that does not go to great lengths to impress, but subtly connects us with its characters and reinforces the things that are most important to us.

Tagged adventure game, amanita design, indie game, Machinarium, Puzzle, Steam