Editorials

Does the term ‘Video-Game’ need to be redefined?

October 20, 2014, Author: Jasper Pickering

video game |ˈvɪdioʊˌɡeɪm|

noun

a game played by electronically manipulating images produced by a computer program on a television screen or other display screen. – Oxford English Dictionary

Video-games have been hard to define in recent years, as genres spin off into hard-to-explain terms with increasing complexity and purpose. ‘Electronically manipulating images’ seems to be a good way to put any creative work with any sense of agency under this umbrella, but the term ‘game’ implies that the purpose of its creation is to be enjoyed. A ‘form of play or sport’ is a simpler way to define the word ‘game’, and this brings into question, “Is this video-game supposed to be either play or sport?”

There have been video-games made in recent years that do neither of these things. Games such as Dear Esther and Gone Home – commonly referred to as ‘art games’ – often have no ostensible objective or purpose. So why do we still refer to them as video-games? Surely, any media that provides any agency to the audience is worthy of this accolade, no matter how vague the definition can be?

An adventure of ‘nothing in particular’.

Perhaps. This is the common argument; that art games are not – in the strictest definition – video-games, as they are ‘not fun to play’. This debate is valid, to a point. The question that’s asked is, ‘am I enjoying this game?’ when the question should be, ‘am I meant to be enjoying this game?’

This has never been an issue for visual novels, which are still incredibly popular in Japan. Player choice is limited to occasionally selecting a route for the character to take, and the visual novel then guides the story based on this decision before the next choice has to be made. There is less interaction involved in this genre than any other that springs to mind, yet we still class them as video-games, even though they share more in common with books (or ‘choose-your-own-adventure’ stories more specifically).

Like other genres, visual novels can have good titles and god-awful titles. What can be classed as a ‘good’ visual novel is down to the player’s (or reader’s?) investment in the story and characters. Having an emotional tie with the material ensures that the player is engaged enough that they want to continue following the narrative, just like a traditional book.

“We’re big in Japan” – Vague personification of visual novels

Video-games have the capacity to incite a vast array of strong emotions, and it’s often the strongest invocations that leave the biggest impression. There is a reason why the horror genre is one of the most popular in film, because horror films have the ability to build tension and unleash it at any given moment. The sense of sheer terror is only exacerbated by the rise of unease, which helps to punctuate the film’s set pieces. The same can be said for horror games, as the same techniques can be applied. Whether or not they are done well is a different question, however.

The ‘best’ works of art are often the most capable of creating an extreme emotional reaction. If a horror movie were not that scary, it would be considered a bad horror movie, or if a comedy weren’t that funny, it would be considered a Rob Schneider film. This isn’t the case for all content however, as there are plenty of great works that relish in their subtleties, including video-games of a certain pedigree that are often overlooked.

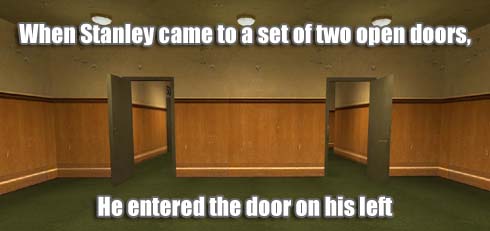

It’s for this reason that art games can be dismissed as things that do not elicit any sense of ‘fun’ or ‘sport’, as few are often permeated with an obvious point of emotional reaction. The Stanley Parable for instance, highlights the monotony of its gameplay through its deadpan narrative, and restricted agency. This doesn’t make it a bad game even in the slightest definition, but it does make it different. At first glance The Stanley Parable could be described as a first-person puzzle game, one not too dissimilar to Portal. It is, however, its own separate entity, with a blurry definition that struggles to come up with its own term. Yes, the game can be very funny, but could it be defined as a ‘comedic game’? Perhaps not. After all, it can become very dark without a moments hesitation. It’s a rather schizophrenic experience that changes throughout the player’s progression.

The Stanley Parable is an experiment in social behaviour and interaction. It’s an art game with one core concept that drives the rest of the experience; how should you respond to authority? It clearly takes much of its influence from the infamous Milgram Experiment back in the 60s, yet by using this one simple concept, a new experiential form of interaction has been created. I would argue that The Stanley Parable shares many similarities with visual novels; the narrative develops based on the choices that Stanley makes at fixed points of the story, leaving multiple endings that can be revisited on later playthroughs. Of course, The Stanley Parable isn’t a visual novel –not by the standards of preconceived genres anyway.

Or did he…

As video-games as a medium further develop, new ideas and concepts are being executed that challenge presuppositions and biases that we ourselves assert. The standard tropes that define what a film or piece of literature can/should be cannot be applied to video-games in the same way, and they should be treated with this in mind. Video-games are still a relatively new platform for creativity, and the theories that may have applied to the definition of a video-game twenty years ago may not be applicable in today’s creative landscape, as new ideas are constantly emerging.

There are design elements now that didn’t exist ten years ago and now they are staples of the video-game format. When Halo introduced regenerative health into first person shooters, it became the norm. Now when a game doesn’t have regenerative health it feels like an inspired design choice that refutes the ‘cliché that has been in place for over a decade.

Video-games are changing constantly to their environment. As the technology develops, so to does the ability to experiment with new ideas and ways of interaction. Just because a game is not fun or sport, does not mean that it is not something of value. Creating new concepts, testing boundaries and challenging what’s possible is part of the development process that has given birth to the genre-defining titles that we know and love today, and will be part of what makes the genre-defining games of the future.

Maybe it isn’t the term ‘video-game’ that needs to be redefined, but our ideas of what video-games have the potential to be.

Tagged dear esther, game design, Gone Home, halo, play and sport, Portal, The Stanley Parable, visual novels