Editorials

Death and Mythology in computer games

November 5, 2010, Author: Sarbjit Bakhshi

Anyone in their thirties or has seen any of the videos of the Angry Video Game Nerd knows, games used to be much harder than they are now.

Not ‘very hard mode’ type hard, but ‘insanely difficult’ type hard. So hard that it would not be unusual to never finish any game you owned. So hard in some cases, that it was literally impossible to complete the game. Jet Set Willy (1984), you have a lot to answer for.

We’ve come a long way since those days from when death and frustration was a ready and realistic end to our play experience. The routine was to pick a game, load it from a cassette to the computer’s memory, play, get frustrated and then die. Game over. Start from the beginning. No restarts, no continues. Sure, it made the rare completion of a game more of a unique pleasure, but mostly, there was little chance you would ever complete or ‘clock’ the game. No glory, no end screen, no DLC. You just moved on to the next game.

The contrast with today could not be greater. Prince of Persia (2008) was a game that would not even let you get close to death. Every time you would get into a position when you were likely to die, your accomplice would save you. The lack of even the mild threat of negative consequences encouraged very louche play (at least in myself). I would play in a semi-disinterested way, trying foolhardy choices just to see what happened before taking the most obvious choices. Rather than finding it liberating, I found it unrewarding and unfulfilling as it felt that nothing I did had any consequence at all.

Similiary, in a more prosaic way, in many multiplayer First Person Shooters, death is simply a delay before you get ‘respawned’ at another geographic point in the game arena.

I would argue that for every life in the game world, there needs to be a sense of consequence. Just like in Simon Weatherall’s recent article about moral choices, we need to feel that our actions have an effect in that game world for it to be believable. This is easily understood in terms of moral choices or simple interactions with other characters. However, what is normally absent is the consideration of our (the player’s) death in the game, and considering how often one would ‘die’ in the games mentioned above, it is a noticeable omission.

The best games, do not neglect this aspect, but make it central to the experience. Silent Hill II (2001) and III (2003) at key points deal with your death and sometimes offer you a glimpse of the consequences of your death in the game world. The player would feel that his/her death mattered, and it was clear what would happen to the game world in your absence. More reason for you to stay alive, more reason for you to try to complete the game.

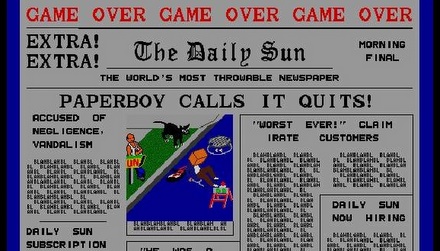

Play Paperboy, know this screen

Apart from making a great game, why else is this important? The classic, long played games (chess, senet, etc.) tie into the dominant culture and come to represent our view of the world (see Margaret Maitland’s article on other games and their significance in Egyptian society here for instance). Every culture has a perception of death and the afterlife, and where these feelings are held, they are heartfelt by people in that society. If a game seeks to draw us in to its play and care whether we ‘live’ or ‘die’ in the game world, I would argue that it needs to consider what the ‘death state’ actually means. For then it ties into our deep sub-conscience and can emotionally engage us further.

I feel that for games that seek to appeal to an adult audience, the games designers need to ask themselves whether ‘death’ is an end point in the game, or a gateway to a further experience. The secular amongst us would argue that death is a finality and the blandness of death (for the poor unfortunate) should be represented by a simple, ‘game over’ screen. For believers, death is only one of many portals we pass through in our existence. Rather being left to chance, the designer should make a conscious choice about what will happen and understand the resultant consequences.

Perhaps a Hindu development team would allow reincarnation to follow death, and depending on your karma bring you back as another character of the story at a higher or lower social setting?

By contrast, a Christian development team could use your death to offer a three-way branching storyline. Get stuck on the ‘hell’ sub-level, level up to ‘heaven’ to end the game or deal with some dlc extra levels in purgatory. Dying, could be even be the true start of the game; albeit an entirely different one from the one you played last. This is something you could either look forward to or do your best to avoid, but the break, relief and/or reward could add a special something.

When this happens, and it makes sense to us in our cultural context, it strikes a chord with us and can heighten our emotional response. The opposite is also true, and perhaps this is a reason why the Final Fantasy XII mythology is so difficult for Western gamers to understand (for a start, there seems nothing *Final* about this *Fantasy*). The game takes place with a set of assumptions about spirituality and what the audience is likely to be able to believe when it comes to post death experiences. FFXII (2006) pushed this to the limit and as such, perhaps left many Western Gamers cold as the entire post death experience was far beyond the limits of our own mythology.

However, it is also true that mythology and concepts about life and death develop and change within a society in relation to social, or spiritual influences from others. The Anglican church in the UK has recently adopted very progressive views which were not the same as the ‘consensus’ of 50 years ago; hence the impending schism with the Anti-Gay communion in Africa. So when Western gamers play games not meant for them, made by development teams around the world, we are building up a pressure that will move our own mythology in that direction. With 390,127 Jedi in the UK today, I believe it is only a matter of time before games players kneel at the shrine of Aries, the God of frustrated gamers in the English Church of Final Fantasy.

Tagged belief, chess, Death, Final Fantasy XIII, frustration, Jedi, Jet Set Willy, mythology, Prince of Persia, PS3, Purgatory, religion, Senet, Star Wars