Editorials

Review scores and why we don’t need them!

September 28, 2011, Author: Trent Pyro

We are a rating nation. These days we’re asked to score everything from make up, restaurant food, all the way to singers, and we do. In this age of internet polls and X Factor, everyone truly is a critic and most of us indulge in a bit of voting more often than we’d like to admit. In the same breath, we’ve come to rely on scores and votes to determine almost every aspect of our daily lives. What’s voted the best bread? Which foundation is most used by the stars? “Ooooh, the new Renault only got 4 stars on Auto Trader? Won’t be buying that then!”

Entertainment is no different. Films, theatre, TV shows and music are all critiqued, reviewed, scrutinised and slapped with a score; games are no different. Journalists and so-called ‘experts’ write sometimes insightful, sometimes awfully biased pieces about the ups and downs of our favourite titles, using heaps of interesting words to take us through the journey without us ever having to experience it for ourselves. All this is secondary, however, to the score at the end; which of course is fundamentally the wrong way round.

How has this happened? Since when did the score matter more than the actual quality of the content? Let’s find out…

The exception to the norm

As regular readers will already know, we here at TIMJ have never used numbered scoring to rate our games, instead utilising a simple, three-tier rating system. This is for a number of reasons, the chief one being that we don’t believe that a number can accurately represent the quality of a game.

Games are unique among entertainment for one main reason; interactivity. Even the most basic games, with linear plot-lines and obvious spawn areas are packed with personal choice. Shotgun or AK? Grenade or no grenade? Where to I cover? Do I hang back or charge in? Each decision affects the final outcome of the situation.

Movies are filmed the way they are, the only real power of change being the editor. Once they’ve finished their job though, that’s it. Rarely will a film get a re-cut, and even then only if it’s successful enough to warrant one. We see it as is; as the director and editor wanted it. We have no choice in whether the hero succeeds or fails, if a supporting character lives or dies and whether the world is saved or doomed. We sit back and enjoy a hand-crafted experience; someone else’s vision. Music is much the same, with the artist’s choice of instruments, structure and composition being our lot. Books, comics, TV dramas and even documentaries all share the same lack of interactivity.

Therefore, judging a film, for instance, based on its merits is relatively simple. Every single person who sees the film will see the same images, the same level of violence and experience the same results of the same choices made by the same characters. A reviewer can be totally sure of that and judge the film according to it’s entertainment value by simply combining their personal, sometimes expert knowledge and a general technical critique of the aggregate parts; acting, directing, production design, editing, etc. A game is entirely different. As I illustrated before, each person will have a slightly different experience.

Putting a score on preference?

Here’s an example; Mass Effect. My personal experience of the game included being overjoyed that I could finally be the driving force behind my own sci-fi epic. I was amazed that an exciting cover shooter was so accurately paired with the RPG micro-managing I loved, and being blown away by the exceptional quality of the dialogue and characterisation.

Does this honestly reflect your opinions? Thought not...

Adversely, a friend of mine seemed to focus on the lack of true free choice, the sometimes poor squad A.I., the choppy, pop-in ridden graphics and the shaky cover shooting. We both acknowledged each others positives and negatives, but reached a different outcome. For me, the flaws were acceptable when compared to the quality of the overall product; especially when combined with my personal infatuation with the sci-fi genre. For my mate, it just wasn’t enough to get past the issues and allow him to enjoy the game.

How is this different from a film, I hear you cry? Well, this is where we return to the issue of interactivity; and more specifically, the quality of that interactivity. Player ability is a huge part of enjoying a game, because no-one likes to lose. I generally dislike racing games, partly because I have no interest in the racing sport at all but also because I just suck at them. On the other hand, I’m an RPG veteran and am adept at working with classes, experience and mountains of stat-based equipment to succeed. Naturally I’m going to prefer RPGs to racers because I’m better at them; and I’m quite confident that every gamer uses the same system to judge their purchases in some way.

Random probability matrix

It’s for these reasons that scoring games with numbers is, to me, fundamentally flawed and redundant from the start. It doesn’t take a genius to realise that the more variables involved in something, the more inherently difficult it is to give it an overall rating, especially something as specific as a number.

If two balls are dropped from a height, there are numerous measurable variables to consider when attempting to judge which one will hit the ground first; height dropped from, weight and size being the most prominent. The experiment can be analysed and, combined with foreknowledge of basic gravity and physics you can stipulate that the heavier ball will hit the ground first. You can also offset that with the size, calculating the air resistance and the effect that will have. It’s relatively easy to come out with a rough prediction of what will happen and be correct.

The problem is; games are nowhere near that predictable. There are so many factors involved, in turn warped and changed by the actions and choices of the player. Add to that the certainty of personal preference (although there’s no certainty what that preference will be) and you have an extremely complicated tangle of possible outcomes. How can a simple score possibly express the sum of all those outcomes? It can’t.

The solution is to complicate the prediction; and that’s why we write. That’s why we don’t just muse for a few days and bang out a simple score. We need to be articulate and explain the ups and downs of the game to accurately illustrate to the reader whether it’s good or not. Sure, we can use a score to give a general overview but the words are necessary to give the score context, and this is the inherent issue with scoring systems.

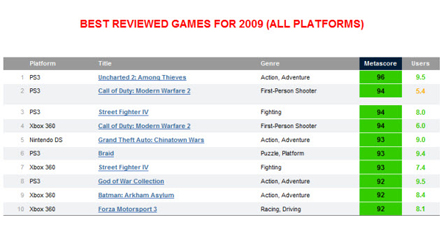

The age of Metacritic

This is not a personal attack on Metacritic; it’s simply the best example to use. It simplifies everything down to a score out of 100. Movies, TV shows and games of all kinds. The Metascore is collated from various numeric scores from established critics and websites. It’s a good resource to see a general overview of what the critics think of it, coupled with public opinion. The problems arise when people start using it as a rulebook.

A game should be bought based on its merits and how they apply to you, offset by its issues. Yet more and more people are buying games based on review scores; scores that we’ve already established cannot give an accurate impression of whether they will actually enjoy the game. This is partly due to the age of convenience, where everything is becoming streamlined and simplified in the name of progress and ease of use. It’s also due to the fact that people are being told that the score is definitive; that is, it should be followed and accepted as the final word on the game. This is entirely untrue and gives way to a culture where ratings mean more than actually quality.

That’s the reason we have worded reviews; so we can explain, in detail, the game in question. So the reader can weigh up the options and decide whether the game is for them. Defaulting to the score and using that as basis for purchase is absurd, but when it’s so much quicker and easier why not do it? The answer is simple; without the context of the written review, the score is useless and misleading.

Nothing is perfect

A big problem is the way the scores are reached. Points are deducted for lacklustre graphics, poor controls and weak plot-lines among other things. Starting at a solid 10/10, demerits are considered and the score is reduced. Sounds fair? Well it isn’t.

Firstly, there is no such thing as a perfect game, yet many publications list a 10/10 as a ‘Perfect Score’… which it is. It’s the top score; it is by definition perfect. This, however, gives the false impression that the game is also perfect, which is impossible. Everything has its technical flaws; perfection can only be achieved when technical mastery is combined with, you guessed it, personal preference.

I think Mass Effect 2 is about as close to perfect as a game can be. It gives me butterflies; that’s how much I love it. Taken purely on technical merit however, it’s far from perfect. The load times are generally poor, the story can at times be contrived and the combat can feel repetitive and a little wooden. Does the score take that into account? Often it doesn’t, and Mass Effect 2 got slapped with many a perfect score, because the overall experience was as close to perfection as possible.

A consistently underrated classic...

In the same breath, Enslaved (another one of my personal faves) was marked down for its uninspired combat and derivative platforming; the overall breathtaking experience wasn’t enough to improve its score. With a story like a wholesome novel, voice and mo-cap acting of exemplary quality and a twist that knocked me for six, the simplistic combat and platforming washed right over me. It felt like a means to an end, a bit of fun to break up the touching dialogue and sweeping story.

The system is flawed and that’s fine. No system is entirely fault-proof but the fundamental problem is that it’s inconsistent. This inconsistency is acceptable when coupled with a detailed review, but when scores are taken at face value there’s no context and no standard.

Keeping the faith

I’m not here to denounce numerical scores. All the biggest mags and sites use them and taken within the context of the review they serve to give a quick, at-a-glance reference of the quality of a game. I’m also not trying to say our system is better and everyone should follow our example.

What I’m trying to say is that the reason we don’t use numerical scoring is simple. We understand that the words in the review are the most important part, not the final score. It’s difficult in this current climate of final ratings and overall average scoring not to default to using that scoring in place of actually figuring it out for yourself, so we remove the issue entirely. Each rating of our system begs an important question; why? Why should I buy it, try it or avoid it? It encourages the reader to actually peruse the review and discover why our writer chose the rating he or she did. It shifts the focus immediately to the words, the most important part. It doesn’t lend itself to meta-scoring and negates the issue of buying on score alone.

This ill-advised purchasing method allows genuinely great games to slip under many people’s radar because they don’t have the scores; and many other lesser games to garner great sales because they do. This article isn’t directed at other sites of reviewers that use numerical scoring systems; I’ve stated that within context they can be useful. Even Metacritic, used as a general reference, can have it’s uses. No, this article is directed entirely at you, the reader, and every gamer out there.

Don’t just take a score at face value. Don’t buy games based on a number that means sweet fuck all when taken out of context. Read the reviews, listen to what the writer has to say about the game and then make your decision. Hell, even asking your mates for their opinions is better than just using a score. Games are such personal, variable experiences that one person’s individual take cannot be expressed through a simple score. That’s why we don’t use them; we want you to read the review because making up your mind isn’t our job. It’s yours.

Tagged avoid it. metacritic, Buy it, numbers, our system, ratings, Reviews, scores, timj, try it